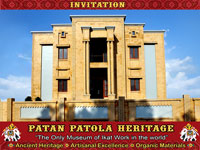

MuseumThe Sanskrit word tapasya, which roughly translates into penance of visceral intensity and frit through years (decades, even centuries) of meditation, may describe the karmic reality of Patan’s Salvi family .We belong to a community of double Ikat weavers. After 15 years of methodical planning on real estate, finance and architecture, and 300 years after our ancestors began to informally document details of the complex weaving technique of Patola weaving, we opened the doors to a private museum in our hometown Patan in north Gujarat in September 2014. This is a vibrant example of seemingly impossible dreams coming true, exemplified by the gleam in the eyes of the youngest weavers in the family- Savan and Rahul Salvi- and our proud uncles, Bharat and Rohit Salvi. Called the Patan Patola Heritage with a board outside including the names of the family’s National Award winners, like Rahul’s late father Vinayak Kantilal Salvi, this is the only such Patola museum in the world. Over 3,000 sq. Of space and three floors, it documents the history of the Patan Patola, a textile that combines techniques of tyeing ,dyeing and weaving. The oldest piece is a tattered red vintage Patola sari wrapped in white muslin and stored in a discreet drawer, the most enticing artefacts are century old artisanal sketches on yellowed and aged paper, made by our ancestors, that document the process of making the Patan Patola. Ikat, an Indonesian word that means to tie, knot or bind, describes a textile which is handwoven after the warp or weft of the fabric is tied and resist dyed for intricate patterns. A single Ikat, where the warp or the weft is tied and then dyed, is practised in various cultures quite prominently in Indonesia, Thailand and Uzbekistan. Double Ikat can also be found in Japan, Guatemala, and in the Indonesian islands of Bali and Kalimantan, but the more complex, Patan Patola variant of double Ikat originated in India. Both the warp and weft are first tied, then resist dyed with extreme precision to retain the dyed designs on the field of the sari as well as on the motifs, without any seeping or blurring . It is the mother of all Ikat techniques. Historically known to have originated in India during the reign of King Kumarpal of the Solanki dynasty in the 12th century, it is treated with reverence by textile scholars as an extraordinary example of weaving. Its samples most of them in the form of a sari hang in every textile museum in the world. Three years back, when this writer met the Salvi family for a book project, they appeared trapped between the weight of a unique inheritance and self generated pressure to “do something for Patola and for Patan”.Strongly insular (they guard their legacy with a do – or – die passion) and ideologically resistant to political intervention, government support and celebrities wanting to wear their saris at fashion vents, the Salvis wanted to chart a distinct path of textile conservation and self conservation. They had been showing their loom and explaining the technique to the hundreds who visit their house every year, but wanted to formalize this ritual. The family’s award winning weavers , as well as Bharatbhai, now a veteran, have also been around the world exhibiting their work at craft exhibitions from Japan to the US. We wanted to conserve and display the Patan Patola legacy without taking financial help or favours from any organization, private or public. W would rather spend every bit of our earnings to conserve the craft mastered by our family. In 2011, Rahul, now 36 had just quit his city job as an architect to become a full time weaver and his cousin Savan, now 30 was studying engineering in palanpur, near patan. Both were focused on getting the museum up and running. The Patan Patola Heritage isn’t one of the most ingeniously cureted museums but it rezones with meaning and purpose. A large loom placed centrally is the first thing you notice. “We have stored the oldest pieces, which are now tattered, in drawers as we want to be selective about showing them. The museum displays award certificates, photographs of celebrities wearing the Patan Patola (Jaya Bachchan and Sonia Gandhi included), old vegetable dyes, old saris woven by the family as well as some newer creations, a 200 year old red Patola frock for a child, an audio visual area for those who want to watch documentaries on the weaving technique, some old spinning looms, a tiny library that includes academic books written on Patola, and samples of single Ikat textiles from various countries. The interiors are made of semi finished wood to retain an unfinished and starkly non industrial look and the prized Patan Patola saris or dupatta length textiles are in glass cases or closed cupboards. Some old pieces now rolled up inside muslin covers have been brought back by the families of our old customers, some of whom are no longer alive. The most striking piece is the Shikarbhat sari completed in 2003,it took three years to weave. It mirrors the scene of a king’s procession a ceremonial elephant with a royal palanquin on it, surrounded by peacocks, tigers, horses and monks. Resplendent in red(red is an auspicious colour in Gujarati tradition and emblematic in the Patan Patola), The shikarbhat first made by our ancestors this one is a replication would have competed with the world’s finest couture. A small piece of fine, diaphanous Dhaka mulmul in butter gold, thoughtfully displayed alongside a matchbox, is also particularly striking. “This mulmul is displayed to bust myths that a Patan Patola can be stored inside a matchbox. That’s not correct. Dozens of visitor’s books, preserved since the early 1930s, reveal the hundreds of textile and conservation experts and student groups from all over the world who have visited the us. In the 1930s, the Patola sari cost Rs 120. Today, the simpler versions of double Ikat cost upwards of Rs 1.5 lakh and onwards, depending on the intricacy of the design. Each sari takes four – six months to weave if two people work on it five days a week. Once you visit this museum, the depth of the red colour keeps returning as a striking memory. The red Patola is worn in traditional Gujarati weddings used both as a shawl draped on brides and grooms, or as a sari by the bride’s mother. Red or any other natural colour used on the Patola apparently never fades or lightens, even when the textile wears away. But the ultimate stamp of this visit is inspiration derived from the passion to conserve a craft, its story and its history.

Patan Potala

Patan Potala